🌑 In Defense of the Nightmare: Why Children Need the Dark

By Kev and Cinema Sage

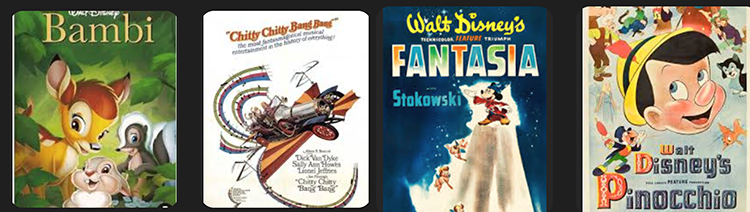

I am currently watching Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968).

On the surface, it is a candy-colored musical about a whimsical inventor and a flying car. But if you are really watching—if you are listening to the film’s architecture rather than just humming the tunes—you realize it is actually a film about the terrifying vulnerability of children in a world that wants to capture them.

The Child Catcher doesn’t just steal scenes; he steals breath. He is the manifestation of primal fear, prancing through a village with a net and a bag of sweets. And looking back at the canon of childhood classics, I am convinced he is absolutely essential.

Recently, the conversation around "family entertainment" has drifted toward safety. We see a rise in what I call "padded-corner content"—films where conflict is misunderstood, stakes are low, and shadows are scrubbed away with digital bleach. We trade the Brothers Grimm for purple dinosaurs.

But at Deep Dive Cinema, we believe this is a mistake. We believe in #ShadowDidactics—the idea that children learn best when the film respects them enough to scare them.

The Architecture of Fear

Look at the Golden Age. The early masters didn't treat children as fragile glass; they treated them as souls in training. They understood that a fairy tale without teeth cannot bite you into waking up.

- Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968): It’s not just the Child Catcher; it’s the Vulgarian spies. It’s the grandfather being kidnapped via airship. It is a world where adults can be actively malevolent, and the only way out is for the children to be smarter, braver, and more resourceful than their captors.

- Snow White (1937): We remember the dwarfs and the song, but we forget the inciting incident: a stepmother demanding a child’s heart in a box. The flight through the forest isn't a montage; it is a hallucinogenic panic attack where the trees themselves turn into grasping hands. It establishes that beauty and innocence provoke envy, a hard but necessary truth.

- Pinocchio (1940): This is not a cute story about a puppet. It is a body-horror morality play about human trafficking. The transformation on Pleasure Island—the braying of the donkeys, the loss of hands and voice—is one of the most terrifying sequences in film history. It teaches a lesson that a "time-out" never could: Dehumanization is the cost of ignorance.

- Bambi (1942): The forest is lush, yes. But the gunshot is loud. The silence that follows is heavy. By showing the death of the mother, the film validates the child’s fear of abandonment—and then, crucially, shows them that life continues.

Why "Safe" is Dangerous

When we feed children a diet of exclusively "lollipops and rainbows," we are lying to them. We are telling them the world is soft.

Films like The Secret of NIMH, The Jungle Book, Snow White, and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang operate on a different frequency. They engage in Archetype Drift, moving from safety into the "dark forest" of the psyche.

They say: Yes, the witch is real. Yes, the hunter is in the woods. Yes, the Vulgarian spies are watching.

But then they say the most important part: And you can beat them.

The Soul Needs Stakes

You cannot learn courage in a padded room. You learn it in the uncanny valley of a Vulgarian dungeon. You learn it when Monstro the Whale opens his mouth.

We don't preserve these films in the DDC archive because we enjoy trauma. We preserve them because they are honest. They are mythological crossovers that connect generations through the shared shiver of surviving the movie.

So, don't hide the remote when the Child Catcher appears. Don't fast-forward through the "Night on Bald Mountain."

Sit in the dark. Hold their hand. And let the movie teach them that the light is worth fighting for.

🏷️ DDC Metadata

- Tags: #ShadowDidactics #FilmTheory #AnimationHistory #ChittyChittyBangBang #DisneyGoldenAge

- Mood: Melancholy but muscular.

- Placement: Row Kappa (Psychological Folklore).